The Narrative Fallacy: Why You Shouldn't Copy Steve Jobs

There are dozens of blog posts about Ben Franklin’s strict daily routine (and they all almost always include this picture), advocating that we should follow suit. Writers love to point out how Maya Angelou made sure she wrote in a hotel room every day to help give her a safe space to work. A young Steve Jobs lived an extremely sparse possession-free lifestyle, and thousands of techies have attempted to emulate this no-nonsense, minimalistic living style.

This kind of hero worship can be a good thing, it can be a guiding light. But this has also given rise to the dramatic oversimplification of entire lives. Headlines like “8 Ways to Think Like Warren Buffett” and “The Socratic Method of Great Living” garner retweets and clicks but they create a terrible feedback loop of writers cherry picking moments from someone’s life, distilling it all down to a blog post or even a book, and then a willing reader to believe that advice is the key to success.

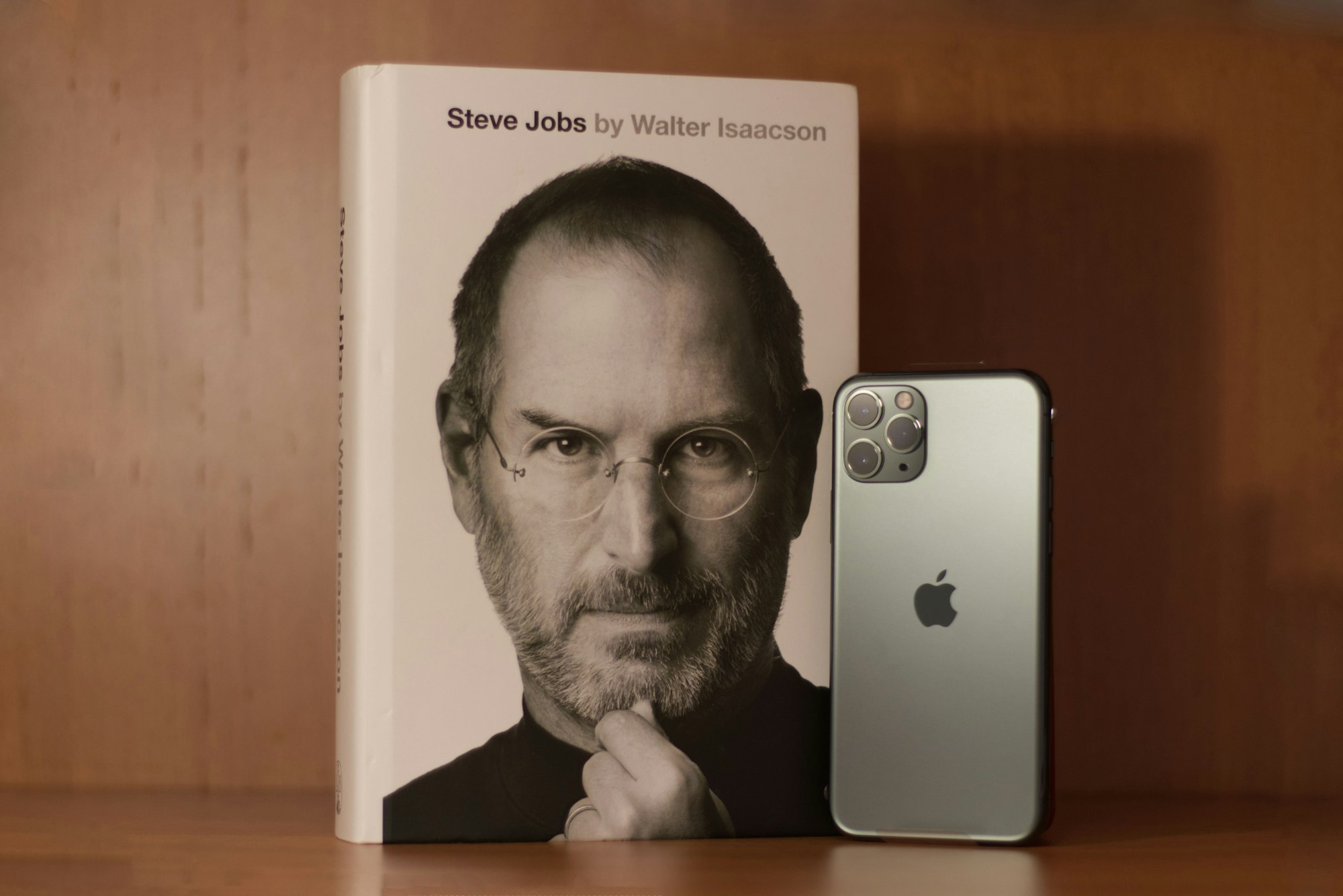

Pictured: A young Steve Jobs in his minimalist apartment. Not pictured: His work ethic and all of his mistakes.

What happens is we have wantrepreneurs and armchair creatives thinking they are walking in the footsteps of the greats by focusing on “productivity hacks” instead of, you know, doing the work.

Even our modern day tycoons are not immune. Square founder Jack Dorsey copied Steve Jobs to an almost comical degree, believing it would make him a better entrepreneur. In Hatching Twitter, Nick Bilton writes about Dorsey’s obsession:

During one discussion with a well-known Apple designer who had been hired at Square, Jack heard that Jobs didn’t consider himself a CEO but rather an “editor.”

Soon Jack started referring to himself as “the editor, not just the CEO” of Square. During one talk to employees, he announced: “I’ve often spoken to the editorial nature of what I think my job is. I think I’m just an editor.”

Jack started saying “No one has ever done this before” about his products, an exact quote from a Jobs interview in early 2010 at a conference.

Jack then adopted Jobs’s terms to describe new Square features, words like “magical,”“surprise,” and “delightful,” all of which Jobs had used onstage at Apple events.

In his bestselling book The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb demonstrates how we humans are obsessed with creating narratives that do not exist, especially when those narratives support our outlook. If we believe that all successful entrepreneurs take naps once a day, we’ll surely remember every biography that mentions how Mark Zuckerberg loves his 2 p.m. siesta.

Read enough and you’ll easily be able to pull anecdotes from anywhere to assemble what all “successful” people should do. “Once your mind is inhabited with a certain view of the world, you will tend to only consider instances proving you to be right. Paradoxically, the more information you have, the more justified you will feel in your views,” writes Taleb. He elaborates on our desire for narrative:

Both the artistic and scientific enterprises are the product of our need to reduce dimensions and inflict some order on things. Think of the world around you, laden with trillions of details. Try to describe it and you will find yourself tempted to weave a thread into what you are saying. A novel, a story , a myth, or a tale, all have the same function: they spare us from the complexity of the world and shield us from its randomness. Myths impart order to the disorder of human perception and the perceived “chaos of human experience.”

Think of the startup myth of a bunch guys in a garage. Or the one that all founders have to work for 80-hour weeks to be successful. Or how every successful designer is obsessive about every last detail. These “keys to success” create a culture and mythology around certain behavior that likely has little to do with the success of the person who practices it.

What is worse, by forcing yourself to adopt the behavior of your idol, you may be suppressing your true temperament, which, it turns out, could be the right mindset for you after all. We don’t need more Mark Zuckerberg-types creating startups or Stefan Sagmiester-types creating art. We need new ideas and new perspectives, which starts with owning who you uniquely are.

Studying the greats in such a simplistic way creates wizardry where none exists and elevates mere mortals to some unattainable standard. Think getting to bed early is the key to athletic performance?

Tiger Woods could stay out until 3 a.m. partying and still dominate you on the golf course (and, well, he kinda did). Is a clean workspace essential for writing? Give Bob Dylan a six-pack of Coors and a notepad in the back of a minivan and he’d still write a better song than most.

Blog posts and books often advise us of the “one thing” we’ll need to really get that dream of ours going. Because, after all, that’s what notable person X did. Articles like this exist mostly because “just put in the work” doesn’t exactly garner a ton of praise or Facebook likes.

Even more puzzling: when we conclude that “all people who want to be successful at X should do Y” we ignore what Taleb calls “silent evidence.” There are a ton of burnt out tech entrepreneurs who went minimalist (à la Jobs) only to see their company fail. There are many writers who created a special writing space like Angelou only to never get a novel published. Stories proclaiming these habits as the “keys to success” rarely delve into the countless number of people that have those exact habits but never shook free from obscurity. Again, The Black Swan:

Let’s say you attribute the success of the nineteenth-century novelist Honoré de Balzac to his superior “realism,”“insights,”“sensitivity,”“treatment of characters,” “ ability to keep the reader riveted,” and so on. These may be deemed “superior” qualities that lead to superior performance if, and only if, those who lack what we call talent also lack these qualities.

But what if there are dozens of comparable literary masterpieces that happened to perish? And, following my logic, if there are indeed many perished manuscripts with similar attributes, then, I regret to say, your idol Balzac was just the beneficiary of disproportionate luck compared to his peers. Furthermore, you may be committing an injustice to others by favoring him.

My point, I will repeat, is not that Balzac is untalented, but that he is less uniquely talented than we think.

It’s impossible for us to take a cursory glance at anyone’s life and boil down their success to a few key character traits. It satisfies our thirst to slap a narrative on everything, but this oversimplification is a disservice. This is not to say that all of our success is the result of luck. For sure, luck doesn’t hurt. But to act like success can be gleaned from a few “tips” is like glancing at the back cover of a book and telling people you’ve read it.

We are living in a complex world and the path to success and fulfillment isn’t a straight line, it’s a labyrinth in the dark. And we all have to find our own way, make our own mythology. It’s a lot harder than following a listicle, but isn’t it a lot more fun?